Progress against Parkinson's disease

UCI Health doctors aim for

earlier diagnosis and treatment

of a mysterious ailment

June 26, 2016

Every evening after dinner, just as the sun is waning in the

western sky, Arthur “Jay” Sagen begins to feel troubled and

turns to his wife of 51 years, Diane, for reassurance. Jay, 76,

was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease—a degenerative

brain disease—six years ago.

He has the typical symptoms of tremors and difficulty

moving. And like many patients in the advanced stages of the disease, he

occasionally experiences delusional thinking or hallucinations.

The behavioral symptoms surfaced a few years ago when the retired

artist and art teacher started seeing black cats squirt by in the periphery

of his vision. Then one day in 2013, Diane, 72, a retired marriage and family

therapist, came home and Jay warned her, “The living room is full of people.”

“It was upsetting, but I had read that there was a possibility of

hallucinations,” Diane says. “His symptoms are usually worse at night

when the light is dimmer and he can misread things. Usually after dinner

we have quite a conversation about who is and who isn’t here.”

For treatment and support the Sagens turn to the UCI Health

Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Program, where experts

recognize the broad array of symptoms and are equipped to help. The

overarching goal of the program is to keep patients functioning as

well—and for as long—as possible while searching for a cure to this

mysterious condition.

“They are so knowledgeable,” Diane says of the program’s staff,

composed of four physicians, including her husband’s physician, Dr. Neal

Hermanowicz, director of the Movement Disorders Program.

About 1 million Americans are afflicted with Parkinson’s disease and

related “Parkinsonian” movement disorders, such as Lewy body dementia.

The risk of developing the disease increases with age, and the average

age of diagnosis is 60. Thus, with an aging population, about 2 million

Americans will be living with the disease by 2030, Hermanowicz says.

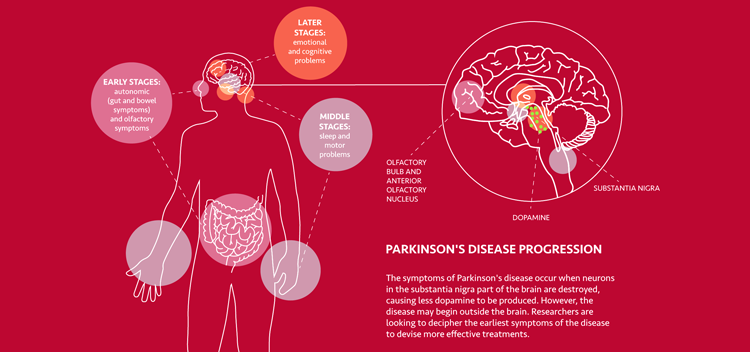

Parkinson’s disease attacks a part of the brain called the substantia

nigra and causes the destruction of cells that produce dopamine, a

neurotransmitter critical to movement and cognitive function. As

dopamine is lost, classic Parkinson’s disease symptoms set in, including

tremor, rigidity, weakness, problems with posture, and behavioral

symptoms such as confusion, anxiety and hallucinations.

Aiming for earlier diagnosis and treatment

It’s not yet clear, however, what causes the disease or even where it

begins. According to research presented at a fall 2015 symposium on the

disease at UC Irvine, the disorder may begin outside the brain—perhaps in

the peripheral nervous system. Pinpointing where the disease originates

and identifying its earliest biological signals, called biomarkers, could

lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective therapies to preserve brain

function, says Dr. Howard Federoff, dean of the School of Medicine and

vice chancellor of UCI Health. Federoff is also one of the nation’s

foremost experts in Parkinson’s research.

“Twenty-five years ago we knew far less than we know today about

Parkinson’s,” he says. “It is our conviction that the earlier the diagnosis,

the better the chance to do neuro-protection.”

Researchers already know that some of the earliest symptoms of the

disease include a deteriorating sense of smell as well as constipation, rapid

eye movement, anemia, anxiety, mood problems and sleep disturbance.

“For the last 10 or 15 years, the emphasis has been not just on motor

symptoms; it has changed to detecting much earlier symptoms, such

as mood changes, sleep changes, bowel movement problems,” says

Dr. Nicolas M. Phielipp, an assistant professor in the Department of

Neurology. “These seem to be symptoms that herald the motor aspects

of the disease.” Phielipp is also part of the Movement Disorders Program

along with Dr. Anna Morenkova; both fellowship-trained in movement

disorders. The fourth member of the team is Dr. Frank Hsu, chair of the

Department of Neurosurgery and an expert in surgical treatment.

In the past decade or two, many treatments for Parkinson’s disease

and other Parkinsonian movement disorders have been tried and failed.

But experts now suggest that perhaps those therapies might work in

patients who are diagnosed earlier—with less-advanced disease—rather

than on patients who are in more advanced stages, Phielipp explains.

UCI Health is at the forefront of research in earlier diagnosis

and treatment. Phielipp is launching a project seeking to identify

early, specific biomarkers of the disease by examining the brain with

sophisticated imaging devices and muscle recordings while individuals

perform simple motor tasks, like tapping their fingers on a table.

“If we can find an early marker of the condition, even without fully

understanding what is going on, trying therapies earlier in the disease

process increases our chances of success in trying to slow down or stop

the disease,” he says.

UCI Health is also part of the prestigious Parkinson Study Group,

a nonprofit organization of physicians and other healthcare providers

from medical centers in the United States, Canada and Puerto Rico

experienced in the care of Parkinson’s patients and dedicated to clinical

research. The group is enrolling participants in several studies, including a

Phase 3 study, called STEADY-PD, to assess a medication called isradipine

and its ability to alter the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

“We have a very large clinical trials program at UCI Health

neurology,” says Dr. Steven L. Small, professor and chair of the

Department of Neurology. “UCI Health neurology is focusing not

only on the state-of-the-art treatments of all neurological diseases but

also on experimental agents that we think can help when other things

can’t help. We have many clinical trial options.”

Gene therapy holds promise

Other studies are underway to assess drugs that impact motor

symptoms. And Federoff is part of a multicenter study group exploring

gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. The first gene therapy clinical trial

for Parkinson’s disease began in 2003, and one decade later five such

trials were underway. The progress reflects an improved understanding of

the brain biology and anatomy, Federoff says.

Gene therapy involves introducing a healthy, functioning gene into

the brain that will begin making a fresh supply of dopamine. Federoff

and his colleagues have devoted many years developing a tool, called a

viral vector, for safely delivering gene therapy to the brain. They disable a

virus, removing its infectious material, and transfer an engineered gene

into the cell.

“The vector is a way to deliver the payload,” he explains. “It’s

engineered to carry the therapeutic gene. The aim is to support the health

of the neuron so it can function properly.”

The researchers have already shown that the viral vector is safe and

well-tolerated by patients, and they’ve learned how to make the vector in large quantities—another crucial step. The next phase of the research

focuses on using the vector to deliver a gene with information capable

of producing a substance called glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor

(GDNF). GDNF is a chemical that may help protect and strengthen brain

cells that produce dopamine. Studies in non-human primates show that

delivering the GDNF gene to the brain causes brain cells important to

dopamine production to stabilize and even regrow.

A Phase 1 clinical trial to test the therapy’s safety and tolerability in 24

patients is now underway at the National Institutes of Health. “We will

have more data than has ever been collected, and I think this will greatly

inform us going forward,” Federoff says.

Preserving quality of life

While future treatments may arrest or cure the disease, UCI Health

professionals today offer a broad array of treatments and support

services to help patients remain as functional as possible. The remarkable

drug levodopa is a mainstay of Parkinson’s disease therapy. The drug

treats the symptoms of stiffness, tremors and muscle spasms.

Some patients are also candidates for deep-brain stimulation, a

surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Deep-brain stimulation involves surgically

implanting a battery-operated device in the brain, similar to a heart pacemaker, that delivers electrical pulses to areas of the brain that

control movement and blocking abnormal nerve signals that cause

tremors, rigidity and movement problems. It is considered for people

whose symptoms respond to levodopa but experience bothersome motor

fluctuations, Phielipp says.

“We have a very active, clinical deep-brain stimulation program at

UCI Health,” he explains. “We do offer this treatment when it’s

appropriate. It’s not for everyone. Patient selection is very important to

its success.”

Another significant focus of the UCI Health program is on the

behavioral symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. While often unaddressed,

symptoms like delirium, hallucinations, anxiety, depression, apathy

and compulsive behavior are not uncommon. Doctors can prescribe

antipsychotic medications to help alleviate behavioral symptoms.

Families are also educated about what to expect and are steered

to resources for support. For a time, Diane and Jay Sagen attended an

exercise group for patients with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers.

Jay is now on a medication to quell the hallucinations, while Diane

attends a caregiver support group and does yoga to alleviate stress.

Jay sometimes doesn’t recognize Diane and demands to know where

his wife is. Occasionally she picks up her home phone and calls herself on

her cell phone so that Jay can “speak to her.”

“I get impatient at times because I know certain things are not true,

and I want him to know it’s not true,” she says. “He takes a low dose of

a medication called clozapine now, and it has helped. And I can get Dr.

Hermanowicz on the phone when I need him.”

About 50 percent of people with Parkinson’s have symptoms of

hallucinations, often mild, says Hermanowicz. The hallucinations are

most commonly visual but also can be auditory, such as hearing people

speak in the home when no one is present, or they may be tactile, such as

the sensation of someone touching them. Delusions are less common but

can include thinking that someone is going to harm them or is stealing

their money, he says.

“Delusions are always unpleasant, nasty and disruptive,” he says. “I’ve

had patients call 911 at 3 a.m. because they thought someone was trying

to break into their house.”

A meticulous evaluation of the patient can help pinpoint what may be

causing the symptoms. Antipsychotic medications are often prescribed,

Hermanowicz says. The healthcare team also works hard to address

depression and anxiety that may accompany the disease.

“Parkinson’s keeps people in their chairs,” he says. “Exercise can play

an important role in treating depression.” Hermanowicz often refers

patients to a therapist at UCI Health who is specially trained in

Parkinson’s disease.

He and his colleagues also steer patients and their caregivers to

support services. Hermanowicz co-founded the California Parkinson’s

Group to foster support and collaboration among individuals and families

in Orange County living with young-onset Parkinson’s disease.

“Quality of life concerns drive our actions,” Phielipp says. “If we don’t

yet have the cure, the main goal of every visit is addressing quality of life.”

UCI Health is especially equipped to address the broad array of

needs, Small says. The UCI Health Department of Neurology has

doubled in size in just last five years.

“As an academic medical center, all our specialists are subspecialty trained,”

he says. “Everyone who takes care of Parkinson’s disease in

our institution has a Parkinson’s disease fellowship. UCI Health

neurology is an huge resource for world-class care in Orange County.”

Learn more about Parkinson's disease at ucirvinehealth.org/parkinsons.

— UCI Health Marketing & Communications

Featured in UCI Health Live Well Magazine Winter 2016